Chapter

6--

Air Pressure and Winds

TEST 3 APRIL 14TH, Chapter 6, 7 and 8.

WIND FLOW CHAPTER 6 VIDEO Part 2 Below (281, 294 Views top bottom)

TEST 3 APRIL 14TH, Chapter 6, 7 and 8.

Air pressure is the pressure exerted by the weight of air above. Average air pressure at sea level is about 1 kilogram per square centimeter, or 14.7 pounds per square inch. Another way to define air pressure is that it is the force exerted against a surface by the continuous collision of gas molecules.

The newton is the unit of force used by meteorologists to measure

atmospheric pressure. A millibar (mb) equals 100 newtons per square meter.

Standard sea-level pressure is 1013.25 millibars. Two instruments used to

measure atmospheric pressure are the mercury barometer, where the height of

a mercury column provides a measure of air pressure (standard atmospheric

pressure at sea level equals 29.92 inches or 760 millimeters), and the aneroid

barometer, which uses a partially evacuated metal chamber that changes shape

as air pressure changes.

Measuring Air Pressure

1 millibar (mb) = 100 Newtons/m2

standard atmospheric pressure (sea level) - 1013.25 mb, 29.92 in. of Hg, 760

mm of Hg

barometer - measures air pressure

mercury

aneroid(without liquid)

barograph

|

|

|

|

The pressure at any given altitude is equal to the weight of

the air above that point. Furthermore, the rate at which pressure decreases

with altitude is much greater near Earth's surface.

The "normal" decrease in pressure experienced with increased altitude

is provided by the standard atmosphere, which depicts the idealized vertical

distribution of atmospheric pressure.

In calm air, the two factors that largely determine the amount

of air pressure exerted by an air mass are temperature and humidity.

A cold, dry air mass will produce higher surface pressures than a warm, humid

air mass.

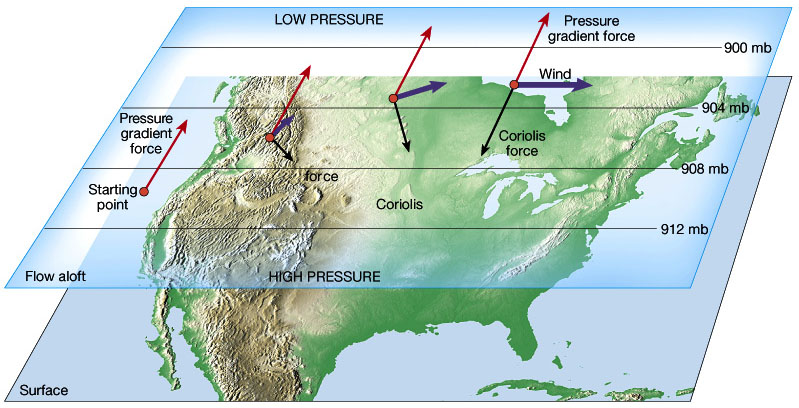

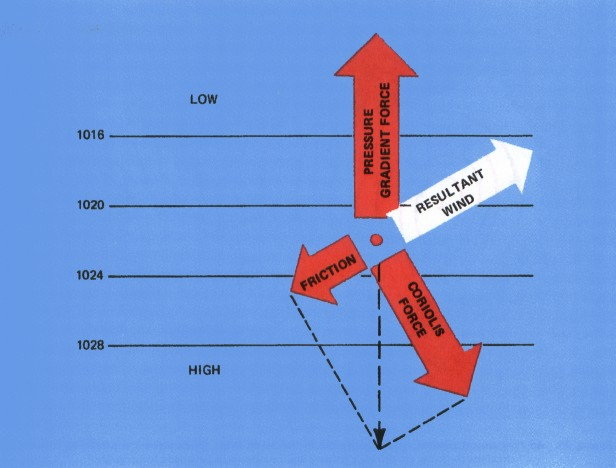

Wind is the result of horizontal differences in air pressure.

If Earth did not rotate and there were no friction, air would flow directly

from areas of higher pressure to areas of lower pressure.

However, because both factors exist, wind is controlled by a combination

(1) the pressure-gradient force,

(2) the Coriolis force

(3) friction.

https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/synoptic/origin-of-wind

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

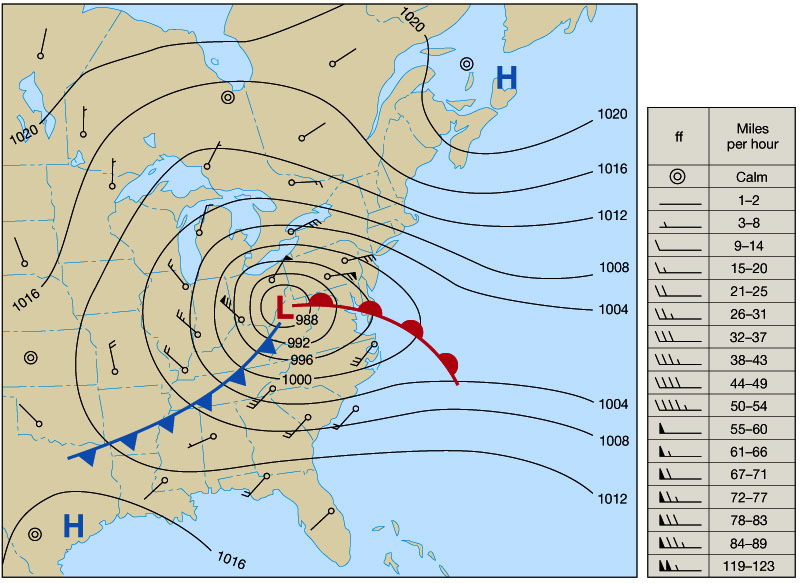

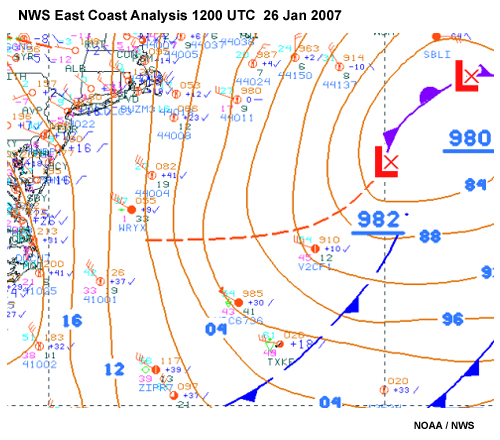

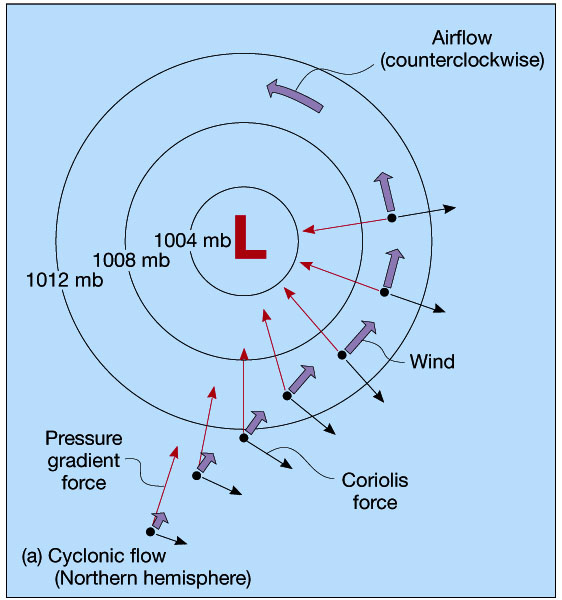

The pressure-gradient force is the primary driving force of wind that results

from pressure changes that occur over a given distance, as depicted by the

spacing of isobars, lines drawn on maps that connect places of equal air pressure.

The spacing of isobars indicates the amount of pressure change occurring over

a given distance, expressed as the pressure gradient.

Closely spaced isobars indicate a steep pressure gradient and strong winds;

widely spaced isobars indicate a weak pressure gradient and light winds.

There is also an upward directed, vertical pressure gradient which is usually

balanced by gravity in what is referred to as hydrostatic equilibrium.

On those occasions when the gravitational force slightly exceeds the vertical

pressure-gradient force, slow downward airflow results.

Pressure Gradient Force

--air flows from high pressure to low pressure

--wind speed depends on “steepness” of pressure gradient

--isobar spacing shows steepness of pressure gradient

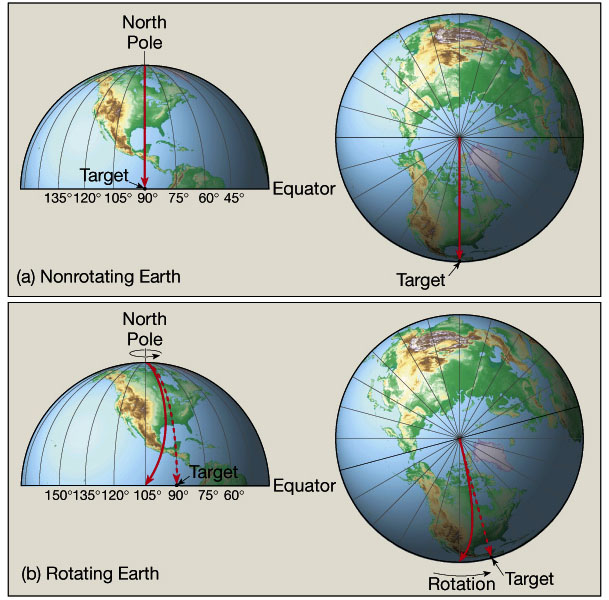

The Coriolis force produces a deviation in the path of wind

due to Earth's rotation (to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the

left in the Southern Hemisphere).

The amount of deflection is greatest at the poles and decreases to zero at

the equator. The amount of Coriolis deflection also increases with wind speed.

Coriolis Effect

wind is deflected to the right (Northern hemisphere)

due to earth’s rotation

effect greater with greater wind speed

effect greatest at poles, decrease to zero at equator

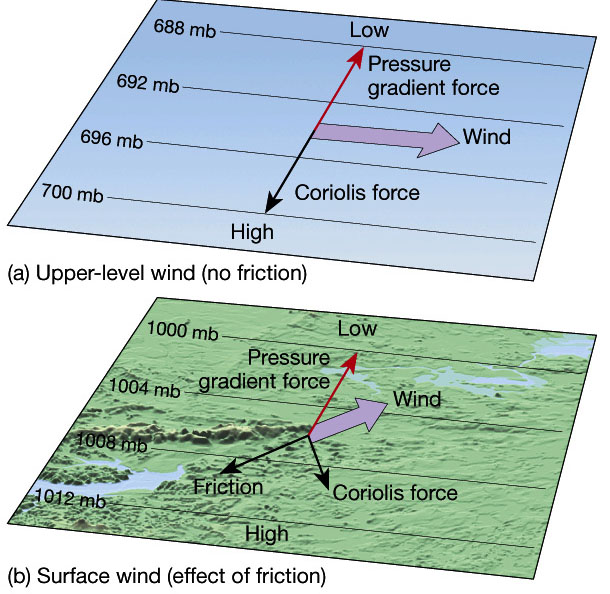

Friction, which significantly influences airflow near Earth's surface, is

negligible above a height of a few kilometers.

Above a height of a few kilometers, the effect of friction on

airflow is small enough to disregard. Here, as the wind speed increases, the

deflection caused by the Coriolis force also increases.

Winds in which the Coriolis force is exactly equal to and opposite the pressure-gradient

force are called geostrophic winds. Geostrophic winds flow in a straight path,

parallel to the isobars, with velocities proportional to the pressure-gradient

force.

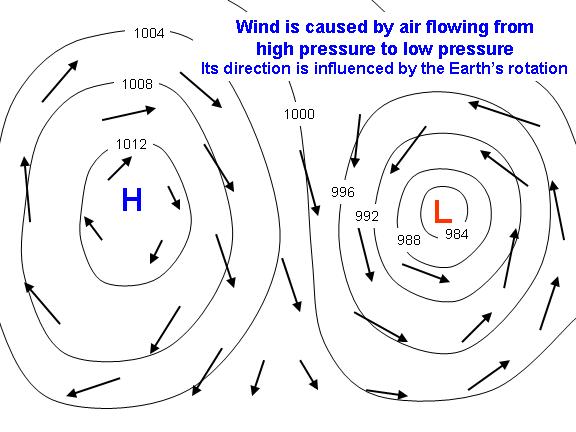

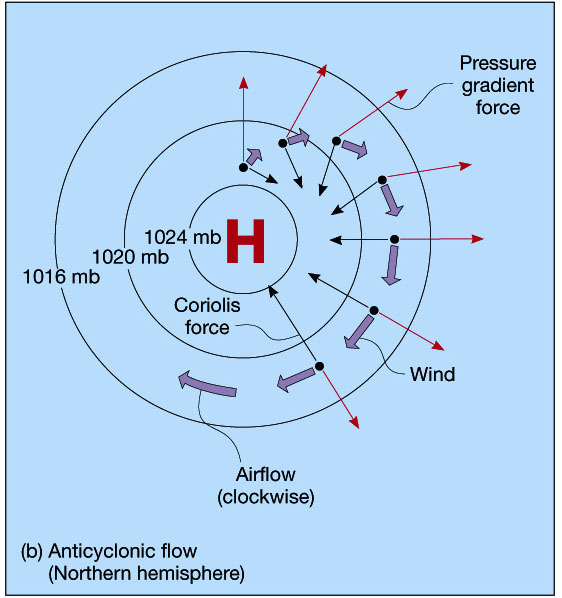

Winds that blow at a constant speed parallel to curved isobars

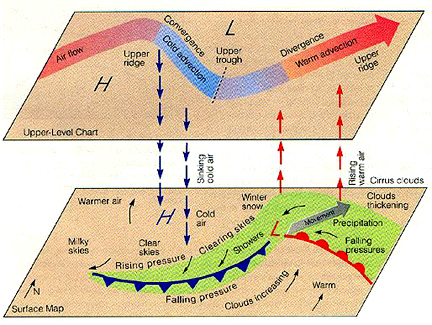

are termed gradient winds. In centers of low pressure, called cyclones, the

circulation of air, referred to as cyclonic flow,

is counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern

Hemisphere. Centers of high pressure, called anticyclones, exhibit anticyclonic

flow which is clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in

the Southern Hemisphere.

Whenever isobars curve to form elongated regions of low and high pressure,

these areas are called troughs and ridges, respectively.

Ridges are associated with fair weather and warmer temperatures

Troughs are associated with stormy weather and cooler temperatures

Near the surface, friction plays a major role in redistributing

air within the atmosphere by changing the direction of airflow. The result

is a movement of air at an angle across the isobars,

toward the area of low pressure. Therefore, the resultant winds blow into

and counterclockwise about a Northern Hemisphere surface cyclone.

In a Northern Hemisphere surface anticyclone, winds blow outward and clockwise.

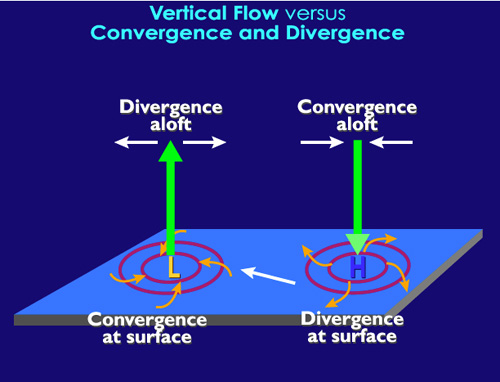

Regardless of the hemisphere, friction causes a net inflow (convergence) around

a cyclone

and a net outflow (divergence) around an anticyclone.

Surface Winds - Friction

surface winds experience friction force

friction force depends on terrain

inflow (convergence) around a Low

outflow (divergence) around a High

A surface low-pressure system with its associated horizontal convergence is maintained or intensified by divergence (spreading out) aloft.

Winds and Vertical Air Motions

air circulating around a High pressure area is sinking

air circulating around a Low pressure area is rising

Inadequate divergence aloft will weaken the accompanying cyclone. Because

surface convergence about a cyclone accompanied by divergence aloft causes

a net upward movement of air,

the passage of a low pressure center is often associated with stormy weather.

By contrast, fair weather can usually be expected with the approach of a high-pressure

system.

As the result of these general weather patterns usually associated with cyclones

and anticyclones, the pressure tendency or barometric tendency

(the nature of the change of the barometer over the past several hours) is

useful in short-range weather prediction.

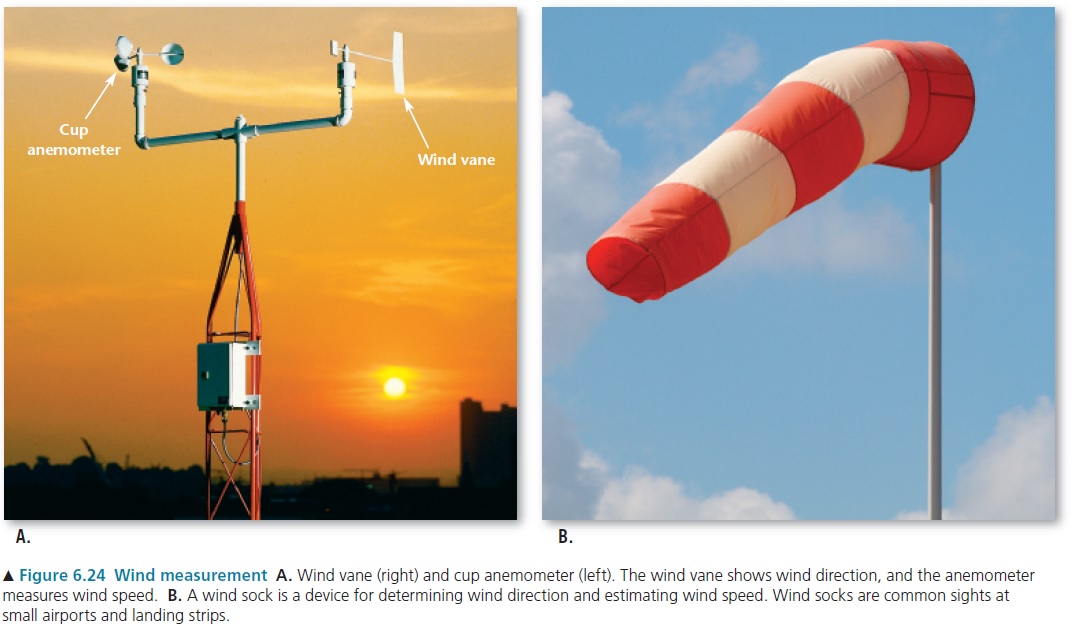

Two basic wind measurements—direction and speed—are

important to the weather observer. Wind direction is commonly determined using

a wind vane.

When the wind consistently blows more often from one direction than from any

another, it is called a prevailing wind. Wind speed is often measured with

a cup anemometer.

Wind Vane

AEROVANE

What to understand- for exam

TEST 3 APRIL 14TH, Chapter 6, 7 and 8.

The 3 forces that move the wind. Wind flow around Low and High Pressure. What is cyclonic flow? What is Anti-cyclonic flow? Where Do you have converging air? Where do you have diverging air? Think about how the air flows around high and low pressure. Horizontally and Vertically

https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/synoptic/origin-of-wind

Surface wind flow around high and low pressure. Wind aloft (above the ground near 30,000 feet) with high and low pressure. Why are winds much faster above the ground.? Forces that make the wind move. Wind is always the direction the wind is coming from.

How do we measure the wind? Wind Direction? What equipement?